It’s summer vacation, a time when most high school students are lying on beaches or spending lazy afternoons in front of the TV. But the teens at Catholic University’s Capitol Classic Debate Institute have been spending long days toiling away in classrooms and computer labs in pursuit of evidence that will persuade judges that theirs is the best argument.

Almost 200 high school debaters traveled from near and far to attend the debate camp in Washington, D.C., and prepare for the 2002-03 National Forensic League topic, which this year happens to be about mental health. Specifically, thousands of high school debaters will be arguing for and against the following resolution: that the U.S. federal government should substantially increase public health services for mental health care in the United States.

Since the topic is a broad one, the debaters are preparing a wide range of affirmative and negative cases on providing and strengthening the following: mental health parity, mental health counseling for people with HIV/AIDS, informed consent in psychiatric research protocols, confidentiality of psychiatric services in the military, mental health care and community mental health care for Native Americans, and community-based mental health care for children and adolescents.

The students at the Capitol Classic Debate Institute, one of a small number of “debate camps” around the country, will return home to participate in a network of high school debate tournaments on both local and national circuits.

The institute, which costs around $3,000 to attend, attracts skilled debaters who are preparing for prestigious national competitions that, if won, can help them earn them admission into the nation’s top universities. From there, many join intercollegiate debate teams and spend weekends traversing the country to compete in tournaments hosted by different universities.

The goals of debate are to train students in the art of public speaking, argumentation, and cross-examination in the context of public policy. To achieve success in the activity, each student must be able to argue both sides of any given topic effectively. During a typical tournament, each debater must support the resolution in three debates and argue against it in three others.

Two Opposing Views Presented

At the first session the students attended, they encountered two contradictory views of mental health and psychiatry as presented by instructors Dallas Perkins and Roger Solt. They sought to educate the high school students about issues related to mental health and present them with the foundations for many of the arguments they would later use in debates.

Perkins, who is the debate coach at Harvard University, presented a critique of psychiatry.

Using sources such as Robert Whitaker’s Mad in America: Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and the Enduring Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill as the basis for his argument, Perkins told the students that over the past few centuries, many people with mental illness have been treated unjustly in the name of American psychiatry.

Perkins discussed methods once used to “treat” people with mental illness, such as emetic drugs, spinning or gyrating chairs to which patients were strapped, insulin coma therapy, and lobotomies.

“These treatments were not based on any firm or even remote understanding of the causes of mental illness,” Perkins argued. “They were mostly about control. The treatments weren’t given to make the patients better—just to make them quiet.”

Perkins also asserted that pharmacotherapy is continuing the abuse of people with mental illness. For instance, the first generation of antipsychotic drugs has been used to control patients in institutional settings, not to treat psychosis. Drug companies have biased the results of clinical trials involving atypical antipsychotic medications, which may not be more effective than the older ones, Perkins added.

He advocated for treating people with mental illness with kindness—but not with medications—until more is known about what causes mental illness.

Students heard quite a different view of psychiatry from Solt, the debate coach at the University of Kentucky. He defended the notion that untreated mental illness is a serious problem in American society, resulting in high rates of suicide, homelessness, and incarceration.

“Although there have been problems with psychiatric treatments in the past, there are now many effective treatments for mental illness,” he argued.

Solt described some of the data showing that drug regimens were successful at combating mental illness and talked about the benefits of psychotherapy.

He advocated for increasing federal funding to the National Institute of Mental Health for the study of serious mental illnesses.

Against Mental Health Services?

For the next several weeks of the institute, the debaters read books and roamed the Internet to gather evidence they would later use to affirm or negate this year’s mental health resolution. They devised many different arguments, including some that might seem far-fetched to the average nondebater.

Said Perkins, “With a different topic, we might advocate sending food to Zambia because of famine conditions causing 30 million people to starve to death.” Debaters on the negative side, he said, “would have to come up with the best arguments they could for letting those people starve.”

This year, the debaters must come up with arguments against the provision of mental health care. During negative strategy sessions, the instructors and students worked together on some of these arguments.

Some students argued that the federal government should not divert more funding to mental health services because it would pull money away from the nation’s military defense at a critical time. A “counter plan” advocated that states, not the federal government, should fund the new mental health services.

Some negative strategies relied on what in debate is known as kritik, which is a more radical and philosophical way of countering an argument. The debaters had a list of required readings, including books by Thomas Szasz, M.D., who asserts that mental illnesses are social constructions, and French philosopher Michel Foucault, who claimed that mental health facilities dehumanize people by segregating people with mental illness, regulating their everyday behavior, and normalizing ideas of right and wrong.

“The postmodern emphasis on social construction is an influential theme in many fields of academia,” said Solt. “So when we apply these theories to psychiatry, that tends to undermine much of the authority of hard science and psychiatry.”

For example, one team could make the argument that since depression is a social construction emerging out of a society where sadness is not tolerated, mental health services are not justified.

“Debate is a polemical activity,” Solt told Psychiatric News. “If someone takes a radical position, it is sometimes harder to negate than a mainstream position.”

Solt said that exposing debaters to radical ideas is educational, but also has its drawbacks. “Sometimes debaters get a warped view of a topic if they are exposed to radical arguments rather than the more mainstream arguments.”

HIV Counseling

First-time debate spectators will feel as though they are sitting in on an advanced foreign-language class without having studied the basics first. The debaters sound more like auctioneers: they deliver their speeches in such a rapid manner that individual words are not discernible to the untrained ear.

At the debate institute, four senior-level debaters who emerged from the preceding debates with the most successful performance competed in the last debate. In that debate, an affirmative team advocated that the federal government should allocate funds to provide voluntary counseling for people with HIV/AIDS, while the other team argued against the funding.

The affirmative team gave evidence that the mental distress and depression, medical problems, and stigma associated with having HIV/AIDS warranted the adoption of the policy, which included an educational component to train health care professionals about how to provide HIV counseling.

HIV counseling would ultimately stem the spread of the disease, the affirmative team argued, by helping patients to overcome problems like depression and receive training about how to adhere to their medication regimens.

The negative team contested the statement that HIV counseling would actually stop the disease from spreading. Furthermore, they argued that the federal government should not be funding HIV counseling when it should be spending money on more important social programs.

The judges ultimately ruled in favor of the affirmative team, determining that the negative failed to establish that it was more disadvantageous to adopt the affirmative proposal than risk further mental distress from HIV/AIDS.

Preconceived Notions

Some of the high school debaters appreciated the opportunity to learn about mental health in the context of debate.

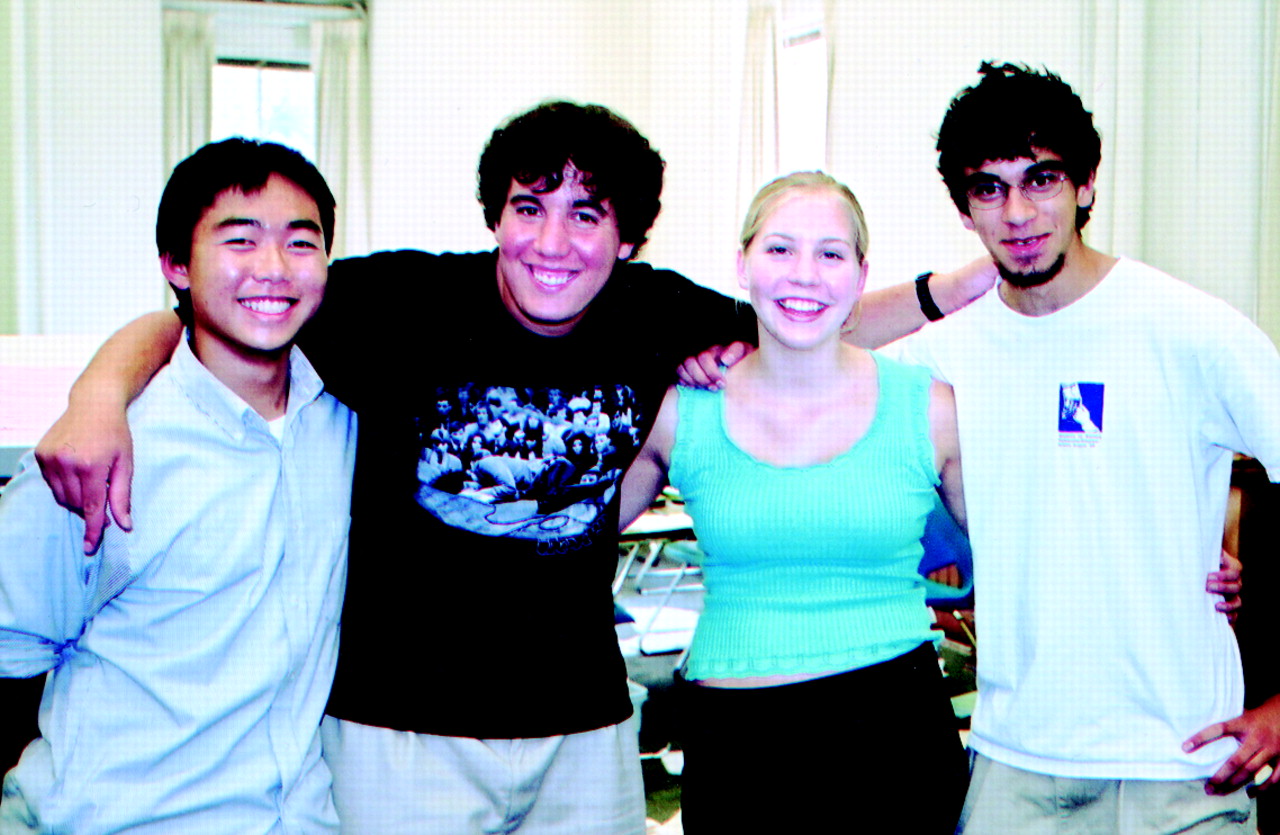

“Debate trains you to make logical, rational arguments on both sides of any given issue,” Arif Lakhani told Psychiatric News. Lakhani is a senior from Atlanta who has been debating for four years and won the final debate with the help of his debate partner, Ohio senior Tony Liao.

Liao added, “We debate about substantive topics that matter in the real world—such as mental health and the political system.”

Josh Foster, another senior from the Atlanta area, likes debate because “you have to think on your feet. . . .You use different pieces of evidence and integrate them into your own arguments. It allows you to draw your own conclusions.”

So what conclusions were the debaters drawing about mental illness?

“I can honestly say that I didn’t know anything about mental illness before coming to this institute,” Liao said. “I had images of padded rooms and straitjackets. This institute has straightened out the preconceived notions I had before.”

He also said that he felt he understood more about the treatments available to people with mental illness since coming to the debate camp.

“You get certain ideas about mental illness from movies, TV, society—you just assume that things are a certain way, and you don’t read much into it,” Lakhani added.

Chris Thiele, a senior from San Antonio, Tex., had read books by Szasz before coming to the camp and said they biased him somewhat against the affirmative arguments. Thiele was busy constructing arguments that used Szasz’s claim that mental illnesses were fictitious, but as all debaters must do, he also gathered evidence to refute this claim.

“I’ve had friends who have been classified as depressed,” said Thiele, “and they were given drugs. I’ve seen how the drugs affected them and how they changed.”

Said debate instructor Solt, “One of the reasons I like this topic so much—aside from the fact that it is important—is that it has some implications for all of these students’ lives.”

More information about this year’s debate topic and related activities is posted on the Web at www.debate-central.org. ▪

link