Patient characteristics for the pilot cRCT

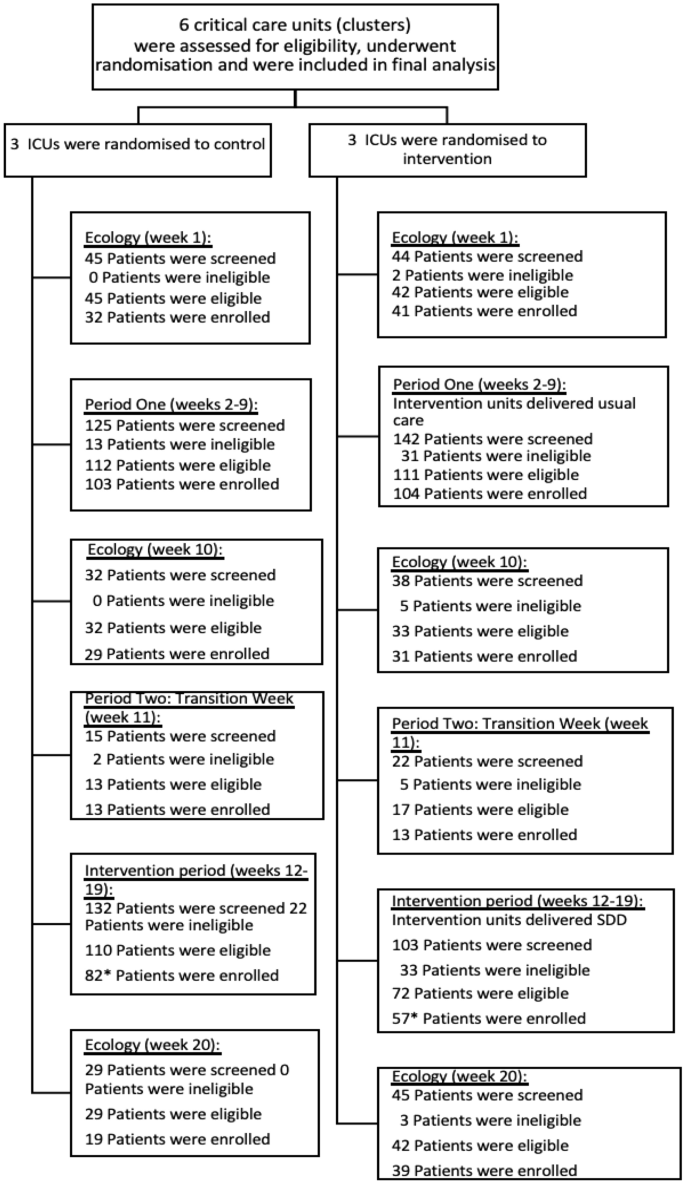

Enrolment across the baseline, intervention and ecology study periods are shown in Fig. 1.

Patients were well balanced across treatment groups and time periods (Table 1). The mean age of patients was similar in Periods One (33.3 months in the usual care sites and 31.5 months in the intervention sites), and Two (28.0 months in the usual care sites and 25.0 months in the intervention sites). Over 63% of the patients were male. The PIM3 score was similar across treatment groups, with a median predicted mortality risk of 2%. The most common primary diagnostic group of the recruited children was respiratory (43%), followed by cardiac (23%).

Parent and staff characteristics for the qualitative study

A total of 65 parents of randomised children completed the survey. This included parents who consented to ongoing participation in the trial (n = 63) and some who declined consent (n = 2). 15 were parents (23%) of children in the intervention group (SDD), 24 (36%) in the control (standard care) group, and 24 (36%) during ecology week. The survey was completed by 44 staff members, with 23 (52%) being nurses and 19 (43%) doctors, representing a total of 11 UK PICUs. Six focus groups were conducted, which involved 26 staff members, with 17 (65%) being nurses, 8 (30%) being doctors, and 1 (5%) being a pharmacist.

Objective 1: Willingness and ability to recruit eligible patients

Between 19 September 2021 and 13 February 2022, 539 children were screened for inclusion into the baseline and intervention phases of the trial (Periods one and two), of which 433 (80.3%) were eligible and 368 (84.9%) of these were enrolled (Fig. 2).

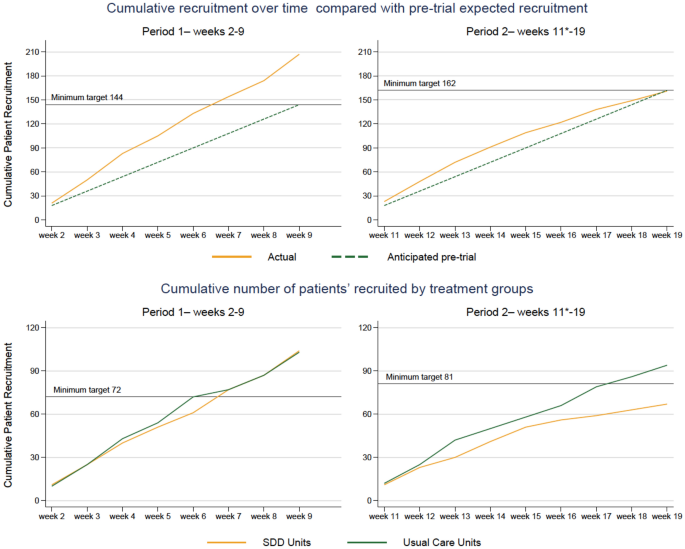

shows cumulative recruitment in the two periods of the study (period 1, left and 2, right). The top panels show actual (orange) versus anticipated (green) enrolment. The bottom panels show enrolment in each period based on the unit randomisation in period 2 (standard care, green; SDD-enhanced infection control, orange).

This was higher than the pre-trial expected recruitment of 306 children across the course of Periods One and Two. In the three ecology weeks a total of 233 children were screened, 223 (95.7%) eligible and 191 (85.6%) were enrolled.

Issues with eligible children being missed were due to difficulties in staff knowing whether children would be ventilated for 48 h, as per inclusion criteria: “We haven’t got a crystal ball, we don’t know.” (P10, FG3, intervention group, research nurse). Some sites screened more than once up until the 48-h window to overcome the risk of not enrolling children who were not originally expected to be ventilated for > 48 h but then required it. Staffing issues due to the COVID-19 pandemic and not remembering to rescreen after the point of admission impacted upon recruitment. Concurrent recruitment of multiple studies and processing of samples in labs that were already overburdened seemed to intensify the issues.

Objective 2: adherence to the SDD intervention

Adherence to SDD intervention

After excluding transition week, a total of 56 children were recruited in the intervention sites, and 55 of them (98%) received SDD treatment (Table 2). Around 68% of eligible children received SDD within the first 6 h as per protocol. Of the expected doses, 9.2% of the oral paste and 9.1% of the gastric Suspension were not administered. The main reasons were being ‘nil by mouth’ (29.5% and 31.1%) and ‘dose missed’ (26.2% and 24.6%).

Overall, focus group participants were mainly positive about the SDD intervention and its use in the proposed trial.

“I’m very aware of healthcare-associated infections, and I think anything that can reduce that has to be good. I would love this pilot to work and this trial to go ahead, to see whether there’s the evidence to back up my hope for it to be of use in reducing healthcare-associated infections. I think it has to be in a way which is acceptable clinically and for families.” (P05, FG2 part 2, intervention site, PI/doctor)

I was interested in the fact that it can reduce the amount of antimicrobials used in that patient, but also in other patients on the unit. That’s what interested me quite a bit was the effect on the microbiological sort of flora (sic) within the unit.” (P18, FG5, control group, PIC consultant).

Challenges identified by staff who administered the SDD intervention included: storage of drug, logistics and packaging, and look of the paste.

“The fact that each of these children had to have their own kit, which seems wasteful. …Obviously, the nurse that’s looking after the patient has got other things to do, she’s now to got to make this drug up in order to give it to the patient. If it was just a bottle in the cupboard she would have done it, but because of the way it’s been dispensed in the fact that each patient has to have their own kit.” (P10, FG3, intervention site, research nurse)

Parents were supportive of a future trial that include the SDD intervention, however, they expressed that they would want the research team to explain better what medication their child is being given.

“Yes, I definitely think that’s important information, it should be clarified. Especially because it’s not typical standard of care, do you know what I mean? Like, I think you should have all the knowledge, as a parent, going into it, exactly. Especially what is being put into your child; you should know.” (P21, mother, SDD)

Adherence to ecology monitoring

Most patients (91–99% across periods) had swab samples taken at admission to the PICU. However, study-specific ecology was impacted by a low rate of consent (44% of enrolled children) for ongoing (twice-weekly) screening swabs. When consent was obtained, adherence to the sampling regimen was good with samples collected for more than 90% of eligible patients at each timepoint. There was good collection of all routine microbiology cultures and antimicrobial administration during the PICU stay.

Objective 3: acceptability of the definitive cRCT

Using a five-point Likert scale ranging from very unacceptable to very acceptable, verbal responses and handset voting suggested that staff involved in the PICnIC pilot trial sites found the proposed trial acceptable. All (n = 26) stated they would be interested in participating in the proposed PICnIC trial and no staff (ranging from senior used the voting poll system (n = 24) felt the trial was unacceptable, most indicating it was acceptable (17/24, 71%), or very acceptable (4/24, 17%), while a couple of respondents (2/24, 8%) were neutral.

“I think acceptable. I would say acceptable with, clearly, the feedback we have given. It needs a bit of finetuning.” (P01, FG1, intervention site, research nurse)

All parents who completed the questionnaire (65/65, 100%) and were interviewed (23/23, 100%) stated that the proposed PICnIC cRCT was acceptable to conduct. This included parents who declined consent for some aspect of the trial. Having the option to decline certain aspects of trial involvement, such as additional samples, appeared to make the pilot trial more acceptable to parents.

Amongst parents, all of them indicated they considered a definitive trial of SDD in the UK PICU setting acceptable.

“I said to the nurse at the time as well when I read it, ‘You should definitely roll this out into different intensive care units around the UK or further afield’. Like I say, it can only benefit.” (P9, father, SDD).

“It just makes sense to do the study across the whole of the UK, increase the accuracy of the study. Yes, I think it’s a good idea.” (P15, Father, Control).”

Parents viewed the intervention as non-invasive and were generally satisfied with the provision of information about the nature of the trial, perceiving a low risk from their child’s inclusion in the study.

Some parents (2 control, 4 intervention) hoped or held the misconception that their child would directly benefit from the study:

“From a point of having it, being in his system, there, ready, it’s just another thing, isn’t it? It’s like another protective layer almost, for him to have.” (P23, mother, SDD).

Acceptability and understanding of randomisation

Overall, parents acknowledged the importance of randomisation in a study such as PICnIC and trusted that the practitioners would “treat the study in an ethical manner” (P15, father, control).

Two parents thought the question of randomisation was hard to answer, as it would depend on how sick the child is and whether the benefits outweigh the risks.

“For me, personally, if my son was really very ill, which he was at one point, to find out that there could be a medication out there that could help him to not get worse by catching an infection, then I would want him to have it.” (P5, mother, Period One control).

Parents in both control and intervention groups wanted to know more about the actual intervention, rather than the trial arm the child had been randomised to.

“I don’t think it’s as important as explaining what the actual treatment involves and what that means for your child and what the drawbacks could be to the treatment actually. I think that’s more important than knowing whether your child is actually getting the treatment or not for it.” (P7, father, SDD)

“Maybe it’s probably worth saying to them, “Look, this is why we’re giving this to your child because everyone on this unit we’d like to give it because we’re comparing it to another unit who is not having it to see the results.” Yes, maybe we could have been told that information.” (P16, father, control)

Parental understanding and acceptance of SDD intervention

While parents had a rough understanding of the study aims, most of them were not aware of what the SDD medication was.

Only one parent was concerned about the child being given an antimicrobial.

“Oh my God, basically stripping the gut of stuff.” (P11, mother, Period One control). Their aversion to their child receiving the SDD medication was based on previous experience of PICU, when the child had experienced severe adverse events as a result of being given antimicrobials. However, they were open to persuasion if given the right information

“It’s difficult I suppose, it depends on how you pitch it anyway doesn’t it? […] if I think my son is at greater risk because he’s more vulnerable…then I’m open to persuasion.” (P11, mother, Period One control)

Acceptability of sample collection and the importance of being informed

The majority of parents thought that it was acceptable to collect routine samples as “they’re taking them anyway” (P3, mother, control) yet many stated that consent should be sought prospectively for sample collection.

“I think parents would want to know and would want to give consent on providing samples. Obviously, I guess, it’s all about the protection of their child. Knowing where the blood samples are going, who are they going to, what the bloods are going to be used for.” (P2, mother, ecology)

Importantly, all parents who completed the questionnaire (65/65, 100%) and were interviewed (23/23, 100%) were satisfied with the approach to recruitment and consent (Tables 3 and 4) stating that the proposed PICnIC cRCT was acceptable to conduct.

Objective 4: estimation of recruitment rate

Characteristics of participating sites

Overall, the sites participating in the study were a representative mix of small and large PICUs with a broad case mix of cardiac and general admissions drawn from across the NHS England geographical region with characteristics that were similar in the 6 sites to the wider PICU admission profile in the UK (Supplementary Table 2).

Characteristics of participating patients

Children who were recruited to the PICnIC study were representative of similar potentially eligible patients (ventilated 3 days or more) in the study PICUs and all UK PICUs but were more likely to be male and with a primary diagnosis of infection when compared with all UK PICUs (Supplementary Table 3).

Statistical approach to a definitive clinical trial of SDD in the PICU setting

The potential recruitment rate for a future definitive cRCT was 3 children/site/week and was estimated by combining a potentially eligible population of 1730 children (estimated from nesting the screening log data from participating PICUs with the national UK PICU data from PICANet) and the overall proportion of eligible children recruited of 85%. This is very similar to the pre-trial estimated rate value of 3.0. The number of eligible children identified from screening logs in the six recruiting PICUs (434) was very similar to the estimate of potentially eligible children from PICANet for these PICUs (464).

Assuming a parallel arm cluster-randomised design with a baseline period, the number of clusters per arm and overall sample size required to detect alternative treatment effects with 90% power and a significance level of 0.05 are shown in Table 4. The number of children per cluster is set at 190 (based on one year of recruitment, including the baseline period), using the ICC observed and mean/proportion among all patients receiving usual care during the pilot cRCT.

The only binary outcome with sufficient frequency to be potentially feasible was any positive microbiology result; however, a detectable difference in this outcome would need to be greater than would be delivered by prevention of all HCAIs. Suitable patient-centred outcomes include scale variables such as duration of mechanical ventilation or days alive and free of mechanical ventilation or length of PICU stay.

Although the study was not powered to compare outcomes between groups, a summary of the potential outcome effects is shown in Supplementary Table 3 to allow consideration of plausible ranges of treatment effects for a definitive trial. As anticipated for a small pilot study, there were not significant differences between the groups in any of the potential outcomes. A summary of the outcomes by treatment group and time period are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Objective 5: understanding of potential clinical and ecological outcome measures

Overall, patient-centred potential outcomes measures had an excellent completion rate, which was similar between groups with a range between 96.3 and 100%.

Characteristics of the patient-centre potential outcomes among all patients receiving standard care (all children in control PICUs and children in intervention PICUs in Period One) are reported in Table 4.

Parental perspectives on clinical outcomes in a definitive cRCT

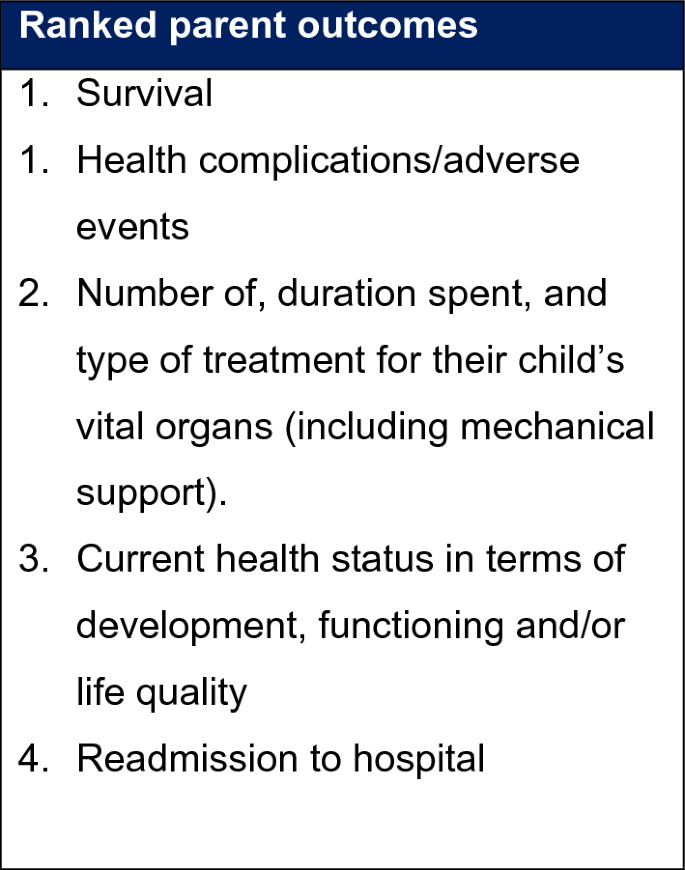

Parents were asked to review the list of outcomes that had been sent to them prior to the interview. In the few cases in which parents did not have access to the materials, a definition of each outcome was read to them, including an explanation about why it is important to explore parents’ perspectives about important outcomes (Fig. 3).

Parent Centred Outcomes for the proposed trial.

Most parents hoped that their child’s quality of life will improve i.e. “getting back eating; obviously, not having relapses; I think getting back to where she was, developmentally, before she got poorly.” (P19, father, control), that “it would reduce the risk of an infection and a need for further intervention” (P02, mother, ecology).

Most parents prioritised outcomes that were included in the list they were provided with, such as reduced likelihood of complications or infections, “less complications because they received the SDD, then I think those would be priority.” (P12, mother, control).

“So, from a parent’s perspective, I’m hoping that this study drives an outcome where secondary infections are less common in children receiving intensive care treatment.” (P07, father, SDD)

Parents were then asked to rank the outcomes listed order of importance from the list provided. The top prioritised outcomes can be seen in Box 1. Survival and health complication/adverse events were ranked joint as most important for the majority of parents.

Although many did not initially mention it, the majority of parents, when prompted, considered survival an important outcome. “I don’t know, the outcome of survival…I try not to think about that really.” (P9, father, SDD).

Other outcomes associated with health complications included infections acquired in the ICU, tolerance of the intervention, the number of specific treatments their child received, and looking and behaving like normal self, i.e., an overall feeling of return to health or normality.

link

More Stories

Bangalore Gastro Centre Hospitals Revolutionizing Digestive Healthcare in Karnataka

Gastrointestinal side effects of incretin-based obesity management medications: insights from healthcare professionals and patients’ experiences

Association between gastrointestinal symptoms and insomnia among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study