As an adolescent and family therapist, I support young people experiencing a range of difficulties from anxiety and depression to PTSD and relationship challenges. Their stories are deeply personal and can be confusing and frightening for parents and caregivers. Yet what I hear week after week affirms that our response to the youth mental health crisis must be both personal and systemic. Multiple societal forces are making it difficult for young people — and many of us — to feel safe, connected and hopeful right now.

The systemic roots

-

Courtesy of Kathleen Osta

Kathleen Osta

Economic inequality and instability directly impact adolescent wellbeing through rising costs, housing insecurity and family financial stress. Limited mental healthcare access due to insurance gaps, provider shortages and cost barriers means many teens go untreated.

- Healthcare system inadequacy creates long waitlists, provider shortages and fragmented care. The medical model often relies heavily on medication without addressing underlying social determinants, with insufficient integration between schools, families, healthcare providers and community services.

- Community and social disconnection compounds challenges as traditional structures weaken. Urban planning that reduces walkable neighborhoods, declining civic participation and increased social isolation all impact mental health.

- Cultural and structural discrimination creates disproportionate burdens for LGBTQ+ youth, racial minorities and other marginalized groups facing hostile environments and lack of representation.

As Paige Swanstein compellingly argued in her piece, College affordability is undermining student mental health. We can’t address one without the other. Progress on youth mental health will necessarily require organizing, cross-sector advocacy and policies that create the economic and social conditions young people need and deserve.

Research shows that 60-70 percent of youth have experienced at least one traumatic event, with higher rates among youth of color and those in under-resourced communities. Yet, most educators and youth workers receive little to no training in recognizing trauma responses or creating healing environments.

I support numerous academically capable young people for whom the school environment is so stressful that their bodies literally break down — migraines, GI issues and panic attacks — making it difficult to attend school consistently, much less perform well on high stakes tests.

The neurobiological foundation

The symptoms most young people are experiencing are a biologically driven response to their environments. Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory, also called “the science of safety,” explains how the autonomic nervous system continuously scans for safety or threat. When young people perceive danger from academic pressure, social rejection, trauma or systemic oppression, their nervous systems shift into defensive/protective states that make learning, emotional regulation and healthy relationships neurobiologically impossible.

How current systems trigger defensive states

- Economic insecurity functions as a chronic nervous system threat. When families face housing instability or food insecurity, young people’s nervous systems experience existential threats. This hypervigilance — wondering “Will I be moving again? Will our utilities be shut off? Will there be food?” — keeps the sympathetic nervous system chronically activated, making sustained attention and academic focus neurobiologically difficult.

- Academic pressure and high stakes testing reproduce inequities and keep many youth chronically activated. Trauma responsive schools that reduce punitive grading, emphasize growth over competition and support student agency see improved student engagement and learning because they reduce cues of threat and intentionally design for safety and belonging.

- Punitive and biased discipline policies trigger defensive responses in young people, creating the appearance of defiance when the nervous system has actually gone into protective fight or flight. Even for young people who rarely “get in trouble,” the constant threat of punishment creates stress and makes it more difficult to focus on learning.

Science provides a clear direction for action

The good news is that recent advances in neuroscience confirm that young people’s brains are malleable and are continuously growing and being shaped by the experiences and relationships they encounter. Mental health, it turns out, is a psychosocial, neurobiological process, not a predetermined fixed state, especially in adolescence.

This means that we can improve adolescent mental health by investing in environments where young people experience safety and belonging, see value in their activities and have systematic access to the resources they need.

Promising systemic responses

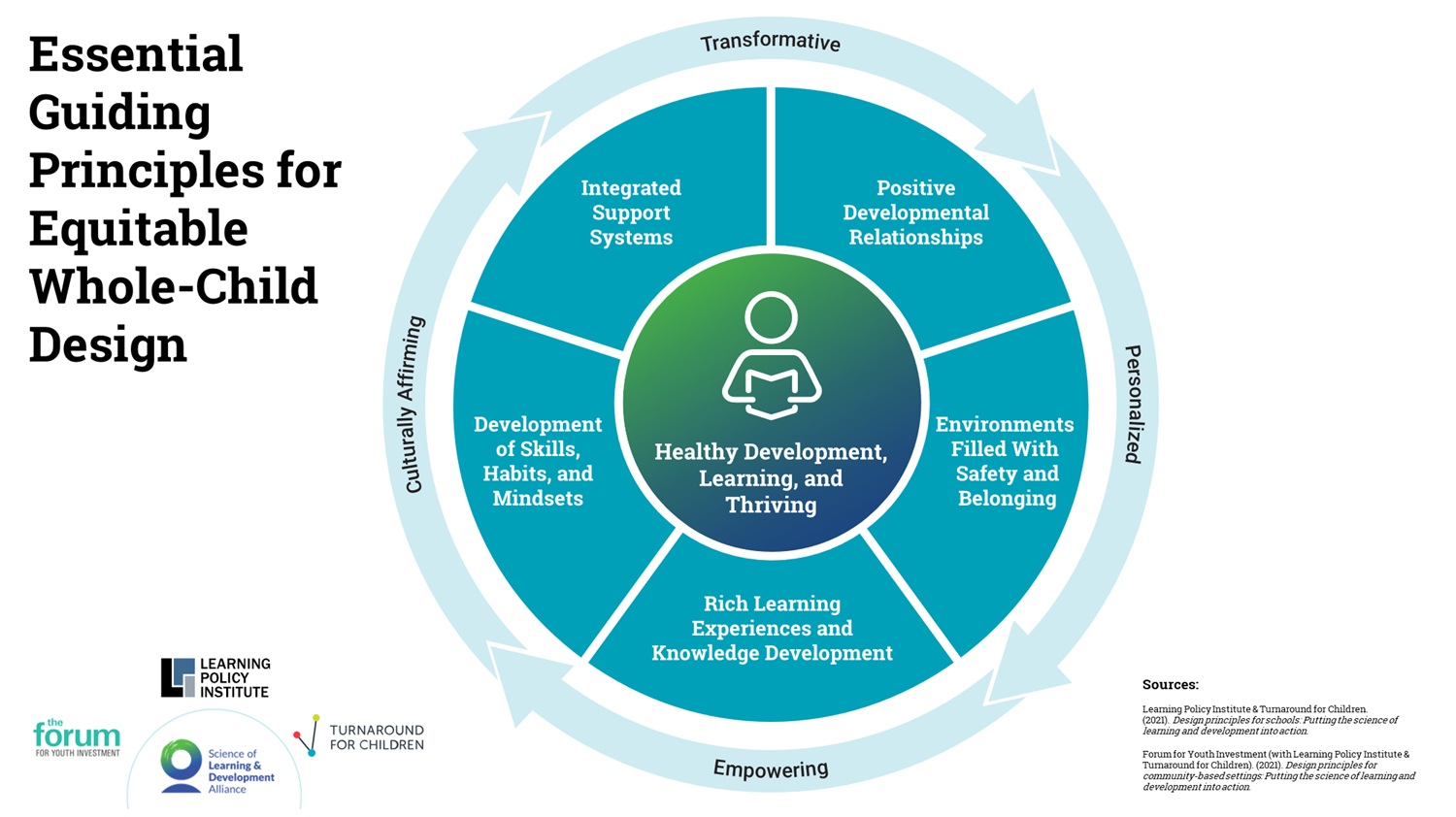

We see some examples of systemic efforts making measurable progress by intentionally addressing essential design principles grounded in the science of learning and development.

- California enacted sweeping legislation requiring mental health education in schools, established the Children’s Behavioral Health Initiative with school-linked services funding and developed the Behavioral Health Student Services Act as part of broader youth behavioral health investments.

- Colorado developed comprehensive frameworks for school behavioral health services including prevention, early intervention and treatment approaches, supporting Building Bridges initiatives integrating schools and community mental health centers.

- Building Assets, Reducing Risks (BARR) addresses systemic issues through eight interlocking strategies in which adults collaborate weekly to review real-time data to understand and respond to students’ holistic needs. Early intervention and linking with community-based services and partners increase students’ access to support when they need it.

- Youth Guidance’s EVOLVE program trains school staff to facilitate relationship-centered circles where young people learn and practice social emotional skills in the context of a safe peer group.

Training existing school and program staff in adolescent development, trauma responsive practices and therapeutic principles could democratize access to mental health by building sustainable institutional capacity and transforming how adults understand and respond to youth behavior, creating healing environments where positive youth development can flourish.

Programs like YouthBuild and Conservation Corps exemplify systemic, cross-sector approaches that support youth mental health through meaningful work and community connection. These programs combine education, job training and community service in environments that inherently address many systemic contributors to youth distress — providing economic opportunity, stable adult relationships and purpose-driven activities that build self-efficacy and social connection. What makes these programs particularly effective from a mental health perspective is their integration of multiple protective factors: they provide year-round structure and support, address economic insecurity through stipends and job training, create opportunities for mastery and achievement and foster deep relationships with mentors and peers. Rather than treating mental health as a separate issue, these programs create conditions where positive youth development naturally occurs through engagement in meaningful, real-world work that benefits both participants and their communities.

The path forward

Mental health support works best when woven into the fabric of youth’s daily experiences rather than delivered solely through clinical services separate from their normal daily lives. These examples demonstrate that successful approaches center relationships, combine immediate service delivery with systemic changes, integrate multiple community stakeholders and address both individual needs and environmental factors. The key differentiator is sustained, coordinated investment in both infrastructure and culture change rather than isolated interventions.

***

Kathleen Osta, LCSW, SEP, is the managing director of field impact and strategy at the National Equity Project where she has been a leader for over 20 years and a practicing therapist providing direct service to adolescents and their families. She is passionate about equipping youth-serving professionals with science-based tools and insights to create conditions for youth thriving.

link

More Stories

HEALTH IN THE KNOW: Free Training Empowers Students to Help in Mental Health Crisis

BU Offers Free Confidential Mental Health Screenings for World Mental Health Day Thursday | BU Today

The impact of physical exercise on college students’ mental health through emotion regulation and self-efficacy